Introduction

When most people think of the term “stress”, they imagine unpleasant emotional responses such as worry, anxiety and depression that result from challenges in life. When viewed in this way, “stress” is something to be avoided. Even thinking about “stress” can be “stressful”. If you look more closely, you will find that stress is much more complicated than this and can have both beneficial and harmful effects on our health. You have probably heard the phrase “the dose makes the poison”. Our knowledge surrounding stress illustrates this beautifully.

What is stress? This question has been debated for years and there is no generally accepted definition. I find it most helpful to consider how the body recognizes and responds to threats. As we evolved, it was important to identify and respond to external threats in the environment (e.g predators or other people). Our brains also learned to anticipate potential threats, which triggers internal emotional responses such as worry and anxiety. The known or perceived threats are called “stressors”, and we have developed multiple physiological responses to them. These stress responses can be beneficial by helping us avoid a threat now and can improve our ability to respond to other threats in the future. This beneficial adaptive response to stress is called hormesis.

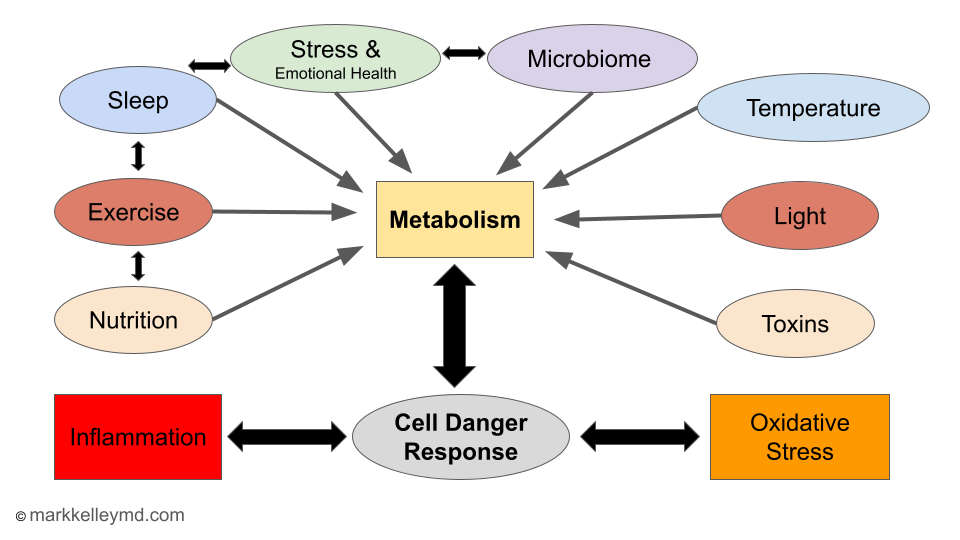

Stress responses can also be a problem when they last too long. These systems evolved to respond to short term threats that go away. Chronic stress responses lead to metabolic dysfunction, which increases the risk of chronic diseases including cancer. There are many different stressors, and their negative effects are additive. Chronic stress also amplifies the negative effects of poor sleep, suboptimal nutrition and a sedentary lifestyle. All 4 of these root causes of metabolic dysfunction and cancer are interconnected through the cell danger response, as described in figure 2 in the introduction to metabolism.

Figure 2: Key features of the cell danger response

Figure 2: Key features of the cell danger response

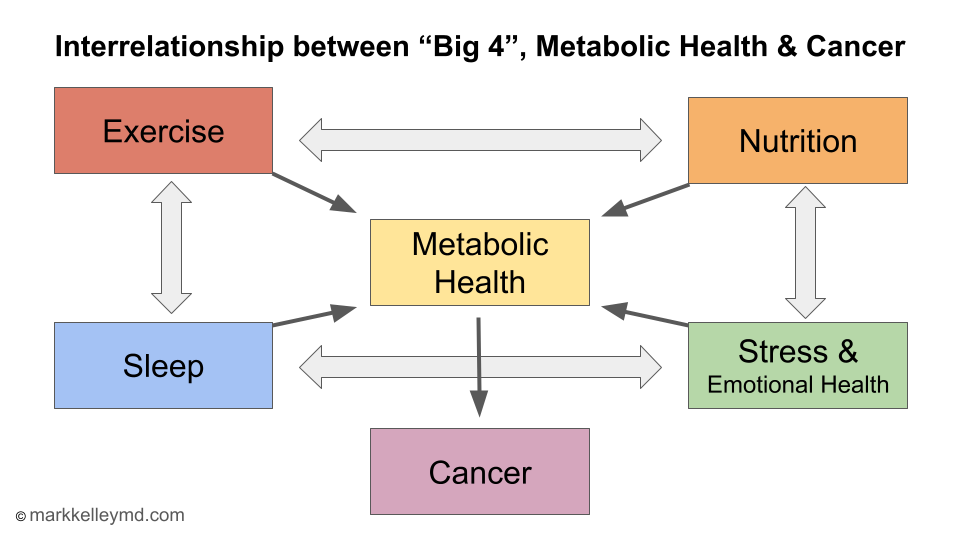

There are several important factors to consider regarding stress, emotional health, metabolic dysfunction and cancer: “Stress” can refer to both the stimulus (stressor) and response (stress response pathways). Stressors can be both external threats from the environment and internal emotional responses to potential threats such as worry and anxiety. Acute stress can be beneficial to health through adaptive responses that increase resilience (hormesis). Chronic stress impairs metabolic health and increases the risk of cancer. Chronic stress and poor emotional health interact with other negative health factors such as a sedentary lifestyle, poor nutrition and poor sleep to amplify metabolic dysfunction and increase the risk of cancer as summarized in figure 3.

Figure 3: Interrelationship between “Big 4”, Metabolic Health & Cancer

Figure 3: Interrelationship between “Big 4”, Metabolic Health & Cancer

Stress response mechanisms

To understand the concept more fully, we should consider the mechanisms involved in stress responses. The brain receives stimuli from the external environment and processes them through neural circuits to generate the physiological changes involved in the stress response. These responses are mediated primarily by the nervous system and endocrine system:

Nervous system

The nervous system is a complex network of cells that transmits signals and coordinates actions throughout the body. It consists of two main parts: the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Here’s a brief overview of the basic components:

-

Central Nervous System (CNS):

Brain: The control center of the nervous system, responsible for processing information, thinking, memory, and decision-making.

Spinal cord: A long, thin bundle of nerve fibers that extends from the brain and runs through the vertebral column, transmitting signals between the brain and the rest of the body. -

Peripheral Nervous System (PNS):

Sensory nerves: These nerves carry information from sensory receptors (e.g., in the skin, eyes, ears) to the CNS for processing.

Motor nerves: These nerves carry signals from the CNS to the muscles and glands, initiating movement and controlling bodily functions.

The PNS is further divided into the somatic nervous system (responsible for voluntary actions) and the autonomic nervous system (responsible for involuntary functions like heart rate, digestion, and breathing). The autonomic nervous system has two components:

Sympathetic nervous system: Activates the “fight or flight” response during stress or emergencies.

Parasympathetic nervous system: Promotes “rest and digest” functions, helping the body recover, conserve energy and maintain homeostasis.

When our brain encounters a perceived stressor it immediately alerts the autonomic nervous system and resets the balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic components. Imagine a seesaw with the sympathetic nervous system on one end and the parasympathetic nervous system on the other. The fulcrum, or pivot point, represents the homeostatic balance of the autonomic nervous system. Activation of the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems lead to distinct and opposing physiological responses.

- Sympathetic activation (stress response):

When faced with a stressful situation or perceived threat, the sympathetic nervous system is activated. This tips the balance, causing a series of physiological changes:- Increased heart rate and blood pressure

- Dilated pupils and increased sweating

- Increased blood flow to the muscles

- Suppressed digestion

- Increased alertness and awareness

- Increased production and release of glucose

These changes prepare the body for “fight or flight,” enabling quick reactions and enhanced physical performance to deal with the challenge at hand.

- Parasympathetic activation (relaxation response):

Once the stressful situation has passed, the parasympathetic nervous system is activated. This helps restore balance by counteracting the effects of the sympathetic nervous system:- Decreased heart rate and blood pressure

- Constricted pupils and reduced sweating

- Increased blood flow to the digestive system

- Stimulated digestion

- Sense of calm and relaxation

- Reduced production and release of glucose

These changes promote “rest and digest” functions, conserving energy and allowing the body to recover from the stressful experience.

The sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems work in opposition, constantly adjusting to maintain homeostasis. The relative activity of each system determines the body’s overall state, allowing it to adapt to environmental demands. In a well-functioning nervous system, the lever should return to a balanced position once a stressor is removed, ensuring optimal health.

Endocrine system

The endocrine system regulates the metabolic function of the cells and organs in the body through the release of hormones. Hormones are molecules that are released from endocrine organs, circulate in the blood, and regulate the physiology of other organs. The major components of the endocrine system are the thyroid hormones, sex hormones (e.g. estrogen, progesterone and testosterone), and the adrenal hormones. All of these components of the endocrine system are under direct control of the CNS, and their activity can be mediated by neural circuits, including those responding to stressors.

The adrenal hormone axis is involved most prominently in stress responses. It is also called the hypothalamic - pituitary - adrenal (HPA) axis. Stressful stimuli are integrated in a brain area called the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus sends signals to the pituitary gland, which increases the production of a hormone called adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH travels through the blood to the adrenal glands located above each kidney where it stimulates production of several hormones including cortisol. Cortisol is the primary “stress hormone” and is increased in response to acute stressors. It serves a beneficial response by activating the immune system and increasing glucose production to respond to that stress. When chronic stress develops, chronically elevated cortisol levels cause many negative metabolic effects including insulin resistance and impaired immune function.

Mechanisms Linking Chronic Stress Responses and Metabolic Dysfunction

Autonomic Nervous System:

Chronic stress leads to an imbalance in the activity of the sympathetic nervous system relative to the parasympathetic nervous system. Increased levels of sympathetic neurotransmitters such as epinephrine and norepinephrine results in:

- Increased blood glucose levels through gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis, and insulin resistance.

- Increased triglycerides through lipolysis; increased LDL and decreased HDL levels.

- Increased muscle protein breakdown.

- Increased blood pressure, increased heart rate, decreased heart rate variability (HRV).

Central Nervous System:

Chronic stress causes structural changes in the brain including reduced nerve cell connections and size in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. These brain areas are involved in memory, problem solving and executive functions such as impulse control and decision making. Chronic stress increases the size of and nerve connections in the amygdala, a brain area involved in regulating fear and stress. Chronic stress is associated with reduced levels of neurotransmitters such as glutamate and GABA which help regulate appetite and energy expenditure.Together, these changes may affect memory, behavior, and appetite and may result in increased energy intake and weight gain.1

Endocrine System

Chronic stress produces persistent activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA). This leads to chronic elevation of the primary “stress” hormone, cortisol. Increased cortisol levels cause metabolic changes similar to increased sympathetic nervous system activity. This includes increased blood glucose levels through production of new glucose from other sources, breakdown of stored carbohydrates and insulin resistance. Increased cortisol also increases triglycerides, fat storage, and increases muscle protein breakdown.

Immune System

The immune system is impaired by chronic stress, primarily through the autonomic nervous system and cortisol. These mechanisms combine to decrease immune function and increase inflammation which results in insulin resistance, oxidative stress and cellular damage. [2] [3]

Mitochondrial Function

Chronic stress also impairs mitochondrial function directly and through sympathetic nervous system activation, increased cortisol levels and inflammation from immune dysregulation.

Chronic Stress in the Modern World

In the modern western world, we are protected from most external environmental stressors such as weather and predators, although safety and physical violence remain a threat in some communities. Unfortunately, there is an unprecedented epidemic of internal emotional stressors that are having a profound effect on our emotional health and chronic stress response. Until recently, individual humans were only aware of their immediate environment, and had limited awareness of threats to others outside that environment. With the advent of mass communication including radio, TV, the internet, and social media, we now can be exposed to any event that causes distress to anyone anywhere in the world. Our brains are biologically wired to pay attention to threats, which can now be accessed 24/7 through social media. It is not surprising that we have seen a dramatic increase in mental health disorders including anxiety, depression, substance abuse and suicide over the last 2 decades. This has occurred in parallel to dramatically increased rates of metabolic dysfunction and chronic diseases including cancer. What is the solution?

Unfortunately, it is not possible to eliminate all stress from your life. The best strategy seems to be to identify the stressors responsible for chronic stress in your life, minimize exposure to them when possible, and incorporate stress management strategies in your daily routine. Taking the opposite approach and adding acute stressors that result in hormesis can also be an effective way to build physiological resilience and balance the effects of chronic stress. Let’s discuss common stressors and the options for managing them.

Common Stressors in the Modern World

There are many potential sources of chronic stress and impaired emotional health. Some are related to past experiences such as childhood trauma, abuse, neglect, and dysfunctional interpersonal relationships. These factors can produce long term psychological and emotional effects, which may be difficult to identify and address. They can be a source of chronic emotional distress with all of the potential negative metabolic effects described above. These issues are addressed most effectively with therapy, which can lead to substantial improvements in emotional and physical health.

Other stressors result from current issues including difficult relationships with family, friends and at work; overwhelming demands from work or caregiving; insecurity due to concern for violence or financial distress, isolation, loneliness, and the sum of the effects of stressful information and conflict from the media, friends and family. It is impossible to completely avoid exposure to these stressors due to work or family obligations. It may be possible to set limits, especially in regard to work hours, exposure to stressful relationships and the amount and type of electronic media we are exposed to. Thoughtful consideration of your daily routine may identify many options to reduce exposure to chronic stressors that can impair your emotional and physical health and wellbeing.

Stress Management Techniques

When stressors cannot be avoided, they must be managed. Many different techniques are available to help manage chronic stress. Most work by affecting the way the brain processes and responds to emotional stressors or restore balance in the autonomic nervous system by increasing parasympathetic activity. Examples include:

-

Psychotherapy: Therapy is essential for unpacking and addressing past trauma, but it can also be helpful for identifying and managing current stressors. A variety of therapy techniques are available such as cognitive therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT). These techniques can help you reframe your thoughts and perceptions, learn and apply new emotional coping mechanisms, and modify undesirable behaviors. Resources: www.betterhelp.com .

-

Meditation and Mindfulness: Meditation refers to a variety of practices that focus on mind-body integration with the goal of “calming” the mind. Mindfulness is a form of meditation that involves focusing attention on the present and not allowing your thoughts to “wander” or make judgements. These techniques have been shown to reduce the effects of chronic stress by restoring autonomic nervous system balance and emotional responses to stressors. This results in beneficial cardiovascular responses (decreased BP and resting HR; increased HRV), improved insulin sensitivity and lipid profiles and decreased inflammatory markers. Resources: www.verywellmind.com ; www.mindful.org www.headspace.com ; www.calm.com ; www.wakingup.com ’ www.hubermanlab.com .

-

Breath Work: Examples include “box breathing”, “physiological sigh”, and Wim-Hof breathing. These techniques increase activity in the parasympathetic nervous system and have been shown to produce the favorable cardiovascular responses described above. Resources: www.verywellmind.com ; www.mindfulness.com ; www.wimhofmethod.com ; www.hubermanlab.com .

-

Movement based meditation and mindfulness: This category includes yoga, Tai-chi and Qigong. These practices include a combination of meditation, mindfulness, breath work, and exercise of varying intensity.

-

Reading and Writing: Both reading and writing can have a calming effect on the mind and may be useful stress management techniques for some individuals.

-

Nature: Being outdoors in nature also has a calming effect for many people. This can result from the peace and quiet experienced in the wilderness, a sense of wonder and connection to the universe, light exposure to regulate circadian rhythms and exercise.

-

Gratitude: Reframing thought processes to focus on gratitude and a positive orientation to life can improve emotional health and reduce stress. This may be particularly applicable for cancer patients, who have or will experience the emotional distress and stress related to the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Focusing on gratitude can improve emotional health and quality of life during this difficult and stressful time.

-

Spirituality and Prayer: Belief in God or a higher power that guides and controls the universe provides peace and comfort. Prayer is an active interaction with God that can seek assistance with stressful life situations. Many people find this very helpful for managing chronic stress and providing a sense of peace and meaning in their life.

Integrating Exposure to Beneficial Hormetic Stress

Stress is inevitable, but we can use it to our advantage through hormesis. As we discussed above, hormesis is a biological phenomenon in which exposure to low doses of a stressor, such as physical exercise or extreme temperatures triggers adaptive responses that lead to beneficial effects on health, stress resistance, and longevity. In other words, low doses of a stressor can stimulate positive adaptations, while high doses of the same stressor can cause harm or damage. When it comes to stress, this is where the dose makes the poison.

Here are some examples of acute, intermittent stressors that can have beneficial health effects through hormesis:

-

Exercise: Physical activity stresses the body, but regular exercise leads to improved cardiovascular and metabolic health, muscle strength, bone density, sleep quality, and mental well-being.

-

Cold exposure: Brief exposure to cold temperatures, such as cold showers or ice baths, can boost the immune system, improve metabolic health, and enhance mental resilience.

-

Heat exposure: Short sessions in a sauna or steam room can improve cardiovascular and metabolic health, reduce inflammation, and promote relaxation.

-

Fasting: Intermittent fasting or calorie restriction can enhance cellular repair processes, improve insulin sensitivity, and may promote longevity.

-

Cognitive challenges: Engaging in mentally demanding tasks, such as puzzles or learning new skills, can stimulate brain plasticity, enhance cognitive function, and delay age-related cognitive decline.

-

Exposure to sunlight: Moderate exposure to sunlight, especially in the morning, can boost vitamin D production, improve mood, and regulate circadian rhythms.

-

Dietary phytochemicals: Consuming plants containing hormetic compounds, especially polyphenols such as resveratrol in grapes or sulforaphane in broccoli, can activate cellular defense mechanisms and promote health.

-

Voluntary emotional stress: Getting out of your “comfort zone” by engaging in challenging, unfamiliar, or ” stressful” activities can help develop brain pathways that enhance resilience and self-confidence.

It’s important to note that the benefits of hormesis occur within a specific dose range. Excessive exposure can have negative consequences, especially for those with pre-existing medical conditions. You should always consult with a healthcare professional before engaging in any new physically stress-inducing activities. It is also best to start slowly and increase the intensity and duration of exposure slowly to allow your body time to adapt.

Other Health Effects of Chronic Stress

Chronic stress can have many detrimental effects on an individual’s physical and mental health. When the body is constantly exposed to stressors without sufficient time for recovery, prolonged activation of the stress response system can lead to various health problems. Here are some of the harmful effects of chronic stress:

-

Cardiovascular disease: Chronic stress can increase the risk of hypertension, coronary artery disease, and stroke by causing persistent elevation of blood pressure, altered lipid levels, insulin resistance and inflammation.

-

Impaired immune function: Prolonged stress can suppress the immune system, making individuals more susceptible to infections, autoimmune disorders, and certain types of cancer. [3]

-

Metabolic disorders: Chronic stress can contribute to the development of insulin resistance, diabetes, and obesity by disrupting glucose metabolism and promoting unhealthy eating habits.

-

Digestive issues: Stress can cause or aggravate gastrointestinal conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), ulcers, and acid reflux.

-

Reproductive problems: Stress can lead to hormonal imbalances that affect fertility, menstrual cycles, and sexual function in both men and women.

-

Musculoskeletal pain: Stress can cause chronic muscle tension or spasm, leading to headaches, back pain, and other musculoskeletal discomfort.

-

Accelerated aging: Chronic stress can shorten telomeres, the protective caps on the ends of chromosomes. This, and other mechanisms can lead to accelerated cellular aging and increased risk of age-related diseases.

-

Mental health issues: Prolonged stress can contribute to the development or worsening of mental health problems such as depression, anxiety disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

-

Cognitive impairment: Chronic stress can negatively impact memory, concentration, and decision-making abilities, leading to reduced productivity and quality of life.

-

Unhealthy coping mechanisms: Individuals under chronic stress may turn to unhealthy coping strategies such as smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, or drug abuse, further compromising their health.

Summary

Stress and emotional health can impact our Metabolic Health in both beneficial and harmful ways depending upon the intensity and duration of the stress. Acute stressors such as exercise, heat and cold exposure can have beneficial effects on metabolism. Chronic stress can impair metabolic health and is a root cause of many chronic diseases, including cancer. Chronic stress should be avoided or limited whenever possible, although this may be very difficult to do in our modern society. To mitigate the harmful effects of chronic stress, it is essential to develop effective stress management techniques, such as regular exercise, mindfulness practices, healthy eating habits, and adequate sleep. Seeking support from friends, family, or mental health professionals can be very beneficial in coping with chronic stress and promoting overall well-being. Stress reduction has beneficial effects on metabolism through several mechanisms including improved autonomic nervous system regulation and decreased stress hormone production. This improves immune function, decreases inflammation and oxidative stress which decrease the risk of cancer.

References:

1 PMID: 26404710

2 PMID: 26086030

3 PMID: 11546738